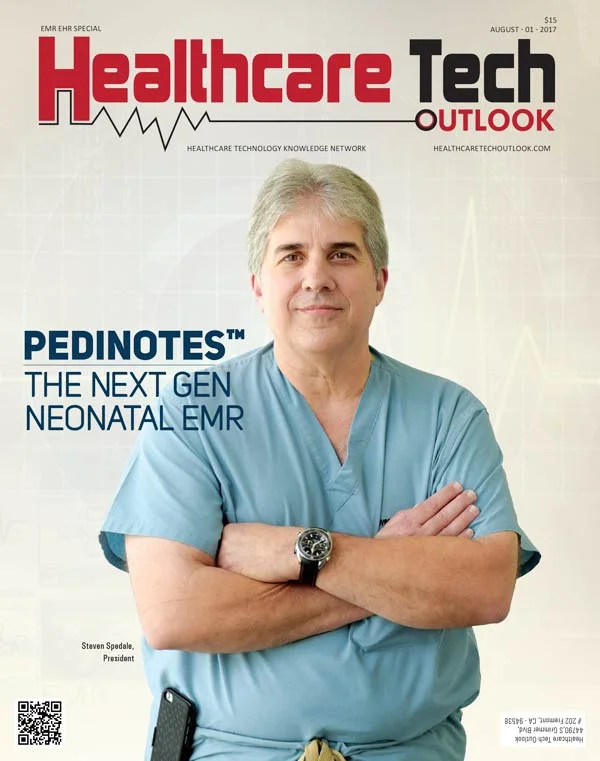

Dr. Steven Spedale, chief of neonatology for Woman's Hospital and Ochsner Medical Center — Baton Rouge, has developed an electronic medical record that doctors actually. One of EMRs' big bugaboos has been physician adoption. Lots of doctors say the software is a barrier rather than a help. Spedale said his PediNotes system is designed to work the way that physicians are trained to practice.

ADVOCATE STAFF PHOTO BY BILL FEIG

BY TED GRIGGS as seen at TheAdvocate.com

Frustration with an electronic medical record system’s limitations pushed Dr. Steven Spedale to develop his own for neonatal intensive care units, and he now is marketing PediNotes nationally.

Spedale is chief of neonatology at the Woman's Hospital and Ochsner Medical Center — Baton Rouge. In 1999, Woman's and Ochsner introduced an electronic medical record. Spedale's practice quickly bumped against the EMR's limitations, limitations the developer had no plans to address.

"He didn't want to do the electronic ordering. He didn't want to do the medication part of the program. Those are the risky parts of the software because if the medication is not right and you order the wrong thing, you could hurt somebody," Spedale said.

So Spedale hired some software developers. They came up with an add-on for electronic orders, then one for medication, then one for billing. The developers also wrote programs that sent physicians updates on their patients.

People started asking Spedale to sell them the add-ons, but he declined. While his software improved the underlying EMR, Spedale didn't think the product was commercially viable as a separate offering. But by 2007, the team had done so much development that Spedale started Tecurologic, a software development company and the eventual parent of PediNotes. By 2012, the company had a commercial version of PediNotes, and Woman's and Ochsner began using the software.

They remain the only users, which has allowed Spedale to break even despite a pretty significant personal investment. But six months ago, PediNotes began a national push. The developers had achieved interoperability, meaning the software can communicate with different computer systems. That's important because PediNotes "sits" on top of the other big EMRs — the Epics, Cerners and Meditechs of the world — and allows the end user to work on one platform.

"So it kind of doesn't matter what hospital I'm in, I can work in the same software program. When you're dealing with critical-care patients, you don't want to have to remember, 'OK, I'm in hospital A, I have to do it this way. I'm in Hospital B, I have to do it this way,'" Spedale said.

EMRs began as something like the digital version of a patient's chart. Electronic health records, or EHRs, were software systems that included EMRs and other general health information on the patient. In theory, EHRs could share that information with other providers. But as Becker's Hospital Review recently pointed out, EMRs and EHRs now share many similarities, and many people use the terms interchangeably.

In 2017, the EMR/EHR market is valued at $29.6 billion, according to Kalorama Information, a medical markets research firm. Although more than 1,000 EMR software companies exist, Cerner, Epic and Meditech control two-thirds of the U.S. market. At present, those firms limit the number of modifications users can make to their products because the developers, like Apple, can't support all of the customizations.

However, Lesley Kadlec, director of practice excellence at The American Health Information Management Association, expects that to change.

As physicians and other clinicians become more adept at using EHRs, they will want to modify them or buy a product that fits the needs of their particular practices.

"I think you'll start to see more and more specialization," Kadlec said.

So it's not surprising that there's a specific product for neonatal intensive care units. NICUs have to monitor everything 24 hours per day. Tracking the food and fluids going into and out of a 2-pound newborn requires specialized tools, she said. It makes sense to design one that helps doctors capture that information as easily and efficiently as possible.

The need to capture specific information by specialty explains why there are EHRs for everything from emergency departments and outpatient surgery to ophthalmology and obstetrics, she said.

Spedale's market is the roughly 800 Neonatal Intensive Care Units in the United States, and then NICUs worldwide. This year, PediNotes has marketed itself at a handful of trade shows and recently launched a national marketing campaign, targeting large hospital systems and their IT departments.

Those systems spend tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars on their main EHRs and as much as 20 percent of that each year for ongoing maintenance, Spedale said. PediNotes might cost a regional-sized NICU $50,000 or $100,000, "not even a blip" on a hospital's IT budget.

Despite the relatively low cost, convincing all of the U.S. NICUs to use his software is unlikely, Spedale said. His initial goal is far more modest: 10 centers in two years.

More specifically, PediNotes wants to sign one of the 120 Meditech centers in the U.S. PediNotes is already being used by a Cerner center and an Epic center.

Once PediNotes hits 10 centers, Spedale plans to double the number of customers every two years. He believes that goal is realistic because his product has a major advantage over most EHRs: it's designed to work the way physicians practice.

"When you are trained clinically, whether you are a doctor, a nurse, a nurse practitioner, whatever, from the way you examine a patient from head to toe, from the way you approach problems, from the way you document problems, there's just a certain standard way that everyone is taught," Spedale said. "So what we really did was put some things in the software to kind of mimic that."

One way PediNotes does that is by putting everything the doctor needs to treat a particular health issue on one page so there's no clicking back and forth from tab to tab. For example, if the issue involves a baby's lungs, the physician can address the patient's breathing, oxygen levels and lab tests on one page rather than clicking back and forth on separate tabs for the lab, X-ray, blood gases or orders.

"That's something that comes from being a physician because that's just how we think. If I'm working on a particular problem, I need all these bits and pieces of information to make a diagnosis, to make a plan," Spedale said. "So what we do is we go in and get all those pieces of information and put it right there for you so you don't have to click around."

The software also allows users to arrange the screens however they wish. So if a doctor wants the patient's vital signs and labs in the upper right corner of the screen, he or she can move it there.

"Whatever works for you to help you take better care of the patient, that's what's important to me," Spedale said. "It's foolish for me to think I know exactly what you need."

Spedale's approach is something of a departure from many EHR products. Although more than two-thirds of doctors use an electronic medical record system, many say the software doesn't help them do a better job. A 2016 study in Annals of Internal Medicine estimated doctors spend close to half their time on EHRs and desk work and just 27 percent with patients

Spedale said one reason PediNotes is different is that it has undergone years of rigorous and brutal testing at Woman's and Ochsner, he said. If something doesn't work for the doctors, they usually let him know within 24 hours.

The whole point of PediNotes is to help the clinician take better care of the patient, Spedale said. Software is a tool. It shouldn't get in the way of the physician or the practitioner or the nurse.

"If my software is making someone change the way they practice medicine, then I think that's bad software," he said.